"It's Our Asses"

Autocrats don’t generally get to pressure people in other countries, but Trump is taking advantage of a more interconnected world and England’s notoriously strict libel laws to cow the once-mighty BBC

Adolf Hitler was never too interested in petitioning the courts of other countries to address his grievances. (Military invasion, as we know, was more his speed.) But he did try, just once, and it didn’t go all that well for him.

The object of his ire was a young American journalist (and future U.S. senator from California) named Alan Cranston, who had noticed discrepancies between the fire-and-thunder German text of Mein Kampf and the sanitized English-language edition being sold in the United States. Cranston didn’t think his fellow Americans were being properly exposed to the dangers of Nazism, so he translated the omitted passages, the ones giving full vent to Hitler’s plans for world domination and eradication of the Jews, and he published them along with his own commentary and a blurb boasting: “Not one cent of royalty to Hitler.”

The German chancellor could hardly sue for libel, since the most damaging words being published were his, but he did sic a team of American lawyers on Cranston for copyright infringement. And he won, sort of. There was no doubt that Cranston had trampled on Hitler’s intellectual property rights, since he had taken the Führer’s words without permission or payment. But Cranston didn’t mind losing in court, or withdrawing his publication from circulation, because publicity from the case had already brought him his desired outcome. “We did wake up a lot of Americans to the Nazi threat,” he recalled decades later.

The world was far less interconnected in the 1930s and 1940s than it is now, and for all the havoc that Hitler, Mussolini and their puppets wreaked on the European continent there were strict limits to their influence elsewhere in the western world. Unfortunately, we cannot say the same for our own times, as Donald Trump has proven by reaching across the Atlantic and managing to compromise and embarrass the BBC, much as he previously compromised and embarrassed CBS, ABC and other US media outlets whose independence was displeasing to him.

Step one, as has been widely reported, was to leap on an editorial mistake. In a segment that aired in 2024, the BBC’s flagship investigative news program, Panorama, spliced together two sections of Trump’s speech to his supporters outside the White House on January 6, 2021 — shortly before they stormed the Capitol building in an attempt to overturn the presidential election that Trump had just lost — and made him sound more belligerent than was justified by the full context of his words.

In an earlier age, this might have gone unnoticed. Indeed, it might still have gone unnoticed, even now, if Trump had not returned to the Oval Office earlier this year and used the power of his office to bring it to light. Yes, it was sloppy, and wholly unnecessary since Trump telling the crowd that “we fight like hell” was bad enough on its own. But it’s also important to understand what kind of journalistic mistake it was. It was a mistake that comes from failing to appreciate the sensitivity of the subject-matter and the need to be extraordinarily careful with it, a mistake that comes from not having the foresight to anticipate what a vain and belligerent American presidential candidate might do in response if elected. The BBC, in other words, was seeing Trump from too much of a distance, much as they might have in an earlier age of foreign correspondents and let-me-explain shows like Alistair Cooke’s Letter from America, an age when the BBC was the authority more than it had to be mindful of authority. And we simply don’t live in that world any more.

Instead, the Beeb has become vulnerable to unbridled American power in the same way that The Washington Post was vulnerable during the Watergate era, when the Nixon administration seized on every small mistake to trash its reporting and smear Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein as dishonest opportunists on the take.

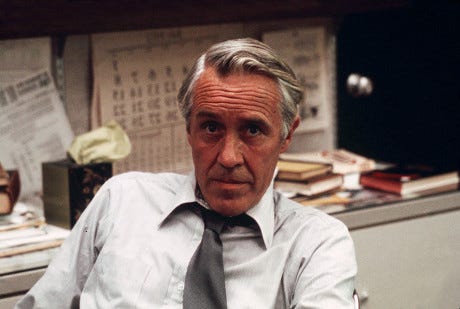

“It’s a dangerous story for our paper. What if your boys get it wrong?” a worried section editor asks Ben Bradlee in the movie version of All The President’s Men.

Bradlee, played by Jason Robards, replies: “Then it’s our asses.”

And the BBC has just had its proverbial ass handed to it, with the director-general and top news executive forced to resign and Trump threatening to sue the corporation for a billion dollars or more. Worse, in stark contrast to Bradlee’s Washington Post, the BBC has now adopted a defensive crouch that is not merely steering it away from lazy editorial mistakes but raising serious questions about its reputation for impartiality and independence.

Nothing exemplifies this better than a last-minute decision to excise a line about Trump from the BBC’s most visible annual lecture series, delivered this year by the iconoclastic Dutch historian Rutger Bregman. Bregman came to international prominence in 2019, when he showed up at the World Economic Forum in Davos and pointed out the absurdity of elite politicians and business leaders who pay scandalously few taxes flying in on 1,500 private jets to bemoan the state of the world climate crisis. Now he is using his BBC talks (known to us Brits as the Reith lectures) to discuss a theme familiar to readers of this Substack: what happens when institutions lapse into what he calls “paralyzing cowardice” and start censoring themselves out of fear of people in power.

The topic could not be more timely, or more bitterly ironic, because it describes exactly what the BBC is doing with him. Long after Bregman had written and won approval for the text of his lectures — indeed, after he had already delivered the first one to a live audience — the BBC decided to take out a line in which he calls Trump “the most openly corrupt president in American history”. The Beeb says it did this at the direction of its lawyers, even though it is an eminently justifiable, even provable, statement — and even though the BBC’s website includes a news story from December 2024 quoting Joe Biden saying the same thing about Trump almost verbatim.

“Self-censorship driven by fear should concern all of us,” Bregman told the Guardian, and he’s absolutely right about that.

It doesn’t help that English libel laws are notoriously deferential to those in power, making it much easier for Trump or other international actors with questionable reputations to apply pressure on their critics through the courts there. In the internet age, when publication is no longer constrained by national boundaries, those libel laws have become a liability for free speech around the world in ways that Hitler could have only dreamed of.

On the plus side, the BBC’s loss of nerve over Bregman has generated more attention for his Reith lectures than they otherwise might have attracted — an echo of Cranston’s experience more than 85 years ago. Only the world doesn’t really need a warning about how corrupt or dangerous Trump is, because we’ve had ten years to get our heads around that. What we need is institutional resistance to his overweening thirst for power and control. And the once-mighty BBC is failing to provide it.